“C’est l’adieu d’un ami, c’est le dernier sourire. Des lèvres que la mort va fermer pour jamais!” — Amour (Haneke, 2012)

Haneke’s film is a moving, terrifying and uncompromising drama of extraordinary intimacy and intelligence. Amour (2012) asks the question of what will survive of us – and what the word means as we approach the end of our lives. Amour begins with a flash-forward sequence. From it, we are left with a devastating memento mori motif. This governs how we react to everything afterwards.

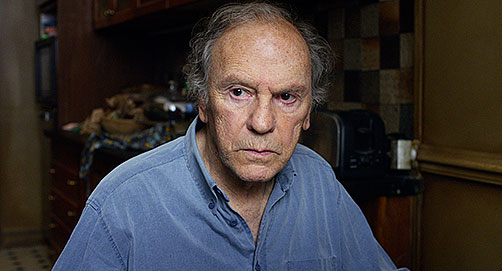

Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva are Georges and Anne, retired music teachers in their 80s. They are living in a handsomely furnished, book-lined, Paris apartment with a baby grand piano. They are happy, affectionate, loving; active and content. We see them attending the performance by one of Anne’s former pupils, and are delighted with his success.

But one day, Anne suffers the first of a series of strokes which paralyse one arm, making playing the piano impossible, accompanied by progressive dementia. Trintignant’s face is etched not merely with the cares of age but dismay and fear: the person whom he loved and loves is beginning to vanish before his eyes.

As Anne’s life ebbs away, so does her identity: is their love itself beginning to be dismantled? The movie reminded me of Proust’s remark about the end of life being a mystery akin to actors laying down a role played for so long that it had become part of who they are.

Having promised the terrified Anne that he would never put her in a home or hospital, Georges is placed under the increasing, insupportable strain caring for her at home. And this in turn colours his difficult relationship with his grown-up musician daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert) and her new husband Geoff (William Shimell) for whose British mannerisms Anne has never greatly cared.

Perhaps the most horrifying parts of the film are the first, tiny indications that something is wrong. Anne awakens in the middle of the night and stares into space — and then assures the baffled Georges that nothing is wrong. The next morning at breakfast, she becomes as still as a statue, her beautiful, mild face as serene as a death mask. When Anne awakens a minute later, with no clue as to why Georges is suddenly so agitated, Riva superbly conveys her sudden, unmentionable thought: is my husband losing his mind?

Haneke shows how in this situation, the family home becomes a barricaded, besieged place and the lives and cares of the outsiders – friends, even close family – are unwelcome and almost meaningless. Their star pupil Alexandre (played by musician Alexandre Tharaud) pays them a well-intentioned but misjudged visit which succeeds only in underlining for Anne the loss of her health, status and music.

With courage and good humour, Georges tackles the demanding new choreography of getting his Anne in and out of her wheelchair, on and off the lavatory. While Anne is still lucid, there is deeply moving gentleness and humour in their relationship. He recounts to Anne the grim absurdity of attending the funeral of one of their friends, in which the Beatles’ Yesterday was played.

But Anne’s light is fading.

In Amour, music is key. Georges and Anne have no religious beliefs, and their music and refined cultural life might have been expected to provide secular consolation. But do they? Perhaps they are simply something else to be taken away, the ability to play and appreciate music simply erode with the physical faculties.

Soon, Georges and Anne are thrown back, almost primevally, on each other.

Love is only going to get them so far, apparently.