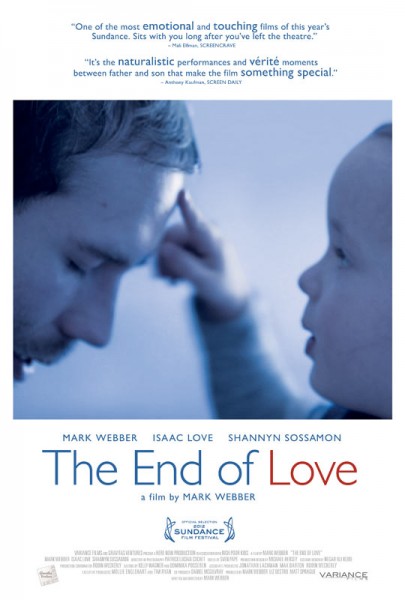

“I want to call the fish ‘Mommy’, Daddy” — The End of Love (Webber, 2012)

Mark Webber’s The End of Love is a kind of therapy for its director. Loosely based on the filmmaker’s life, the movie stars Webber (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) alongside his real-life toddler, Isaac. It explores the challenges of his single-parent household. Intimately shot and almost exclusively focused on the two characters’ daily lives, The End of Love maintains an effectively bittersweet atmosphere that works its quiet spell throughout, although it aims too low to leave a particularly strong impression. It’s simplistic. But, it’s ok.

A far cry from Explicit Ills, Webber’s impressive ensemble piece that served as his directorial debut, The End of Love presents a warm depiction of father-son relations that provides the microbudget alternative to The Pursuit of Happyness, where Will Smith and son Jaden riffed on their own real-life chemistry. I like this better than Happyness. Plus, Isaac is soooooo cute!

Webber pulls off a far more impressive feat by making the hyperactive and consistently distracted Isaac react on cue. It might be one of the most controlled child performances ever put onscreen, partly because the director stays so close to him every scene.

Their moments together give The End of Love a wonderfully naturalistic appeal, but the story can’t keep up. In a somewhat awkward riff on the truth, Webber imagines his situation as the result of his wife’s death shortly after she gave birth to Isaac. In reality, no death took place, but Webber did split up with Isaac’s mother. That backdrop adds a unsettling subtext to the rest of the movie, since it otherwise maintains a basis in reality: Webber plays himself and hangs with known actors who use their real names.

Cameos by Michael Cera and Amanda Seyfried flesh out the blurry line between fiction and documentary, but the overall smallness of Webber’s approach turns The End of Love into something closer to a diary film than a conventional narrative. And so it becomes easy to read his wife’s “death” as an allegory for the actual incident, explaining the introverted quality of Webber’s filmmaking.

However, while his understated approach leaves much to interpretation, it never builds out its basic situation to any meaningful payoff. Most scenes are predominantly composed of Webber and his son engaged in daily rituals, from a messy morning breakfast to an ill-conceived audition ruined by Isaac’s constant interruptions. Tangents involving Webber’s attempts to launch relationships with new women goes nowhere, as does a prolonged sequence in which Webber attends a Cera-hosted party.

Stumbling drunkenly around his famous friend’s abode, Webber’s self-portrait turns into an underwhelming vanity party, providing a reminder of the comparative strength of the scenes he shares with his son.

Let’s face it. The film is never fully realised, and still it is both hard to dislike and difficult to invest in. There are powerful ingredients here, certainly enough to create a deeply felt work. The only thing that gets me is that the movie lacks the additional layers of storytelling necessary for Webber to make the audience feel as close to the material as he does to his son.

Still. It’s worth watching just for the father-son moments. Just ignore the other crap.